Missed Translations Read online

Page 6

I maintained my professionalism and finished what I was doing. Afterward, I walked up to him and said, “Sir, just so you know, I’m not a member of ISIS. I work for CBS News.” He threw his hands up, as if I was attacking him, and said, “I don’t know who you are. Be glad you’re born in this country.”

Sir, I am. Because I have the freedom to call you an asshole in a book. You’re an asshole.

But my skin color never felt as hot as it did when the Trump campaign went to Chicago.

Oftentimes, as a reporter chasing Trump on the trail, you couldn’t help but feel like you were pursuing a carnival disguised as a presidential campaign. It was a big shiny object. Look, there is Trump giving out Senator Lindsey Graham’s phone number! (This happened.) Look, there’s an elephant! No, a real elephant! (There actually once was a real elephant outside of a Trump rally.) Oh my . . . Trump just joked in front of thousands of people that a supporter’s wife was fantasizing about him in bed! (Yes, this happened.) Is that someone dressed like a southern border wall? That’s not even the weirdest thing I’ve seen today, because there’s a man dressed like Colonel Sanders about a hundred feet away. (Both things happened.)

Protesters were a mainstay of Trump rallies, and by March 2016, tempers were at a fever pitch. By this time, Trump was the dominant front-runner in the Republican Party, not just because of high polling but because of actual wins. He had won the New Hampshire and South Carolina primaries by large margins, in addition to the Nevada caucuses. He was winning so much that, as he put it, “your heads will spin.”

One of the big storylines floating around Trump’s candidacy was the amount of violence at his rallies, which many accused Trump of encouraging.

I watched hundreds, if not a couple of thousand, protesters get ejected from Trump rallies over the course of being an embed. It usually went the same way: The protesters made noise. The crowd jeered. Trump yelled, “Get ’em out!” Then he’d go on an extended riff blasting the protesters, maybe mocking them (“Go home to Mommy!”), maybe encouraging supporters to physically harm them (“If you see somebody getting ready to throw a tomato, knock the crap out of ’em.”), maybe inviting peace (“Don’t hurt ’em!”). The protesters were escorted out. The rally (and the show) went on. We were used to this.

Trump was supposed to have a rally in Chicago on March 11, 2016. As soon as it was announced, the chatter of massive protests started making the rounds. A week earlier, Trump addressed a packed airport hangar outside New Orleans, and as he started speaking, he held up, Lion King–style, a baby he had signed in Baton Rouge at an earlier rally. Just in case your eyes glossed over that last sentence, he held up a baby he’d autographed—with an actual marker—weeks before as if he was Baby Simba in The Lion King.

This Chicago rally was supposed to be held at the UIC Pavilion on the University of Illinois at Chicago campus. As I entered the arena hours beforehand, the intensity was already palpable. Hundreds of yelling and chanting young protesters had taken over nearly the entire back half of the arena. Perhaps out of familiarity or wishful thinking, I mentally played down the reports that there would be large-scale protests. This happens at every rally. But it was another reporter standing near me who made me reconsider. Surveying the back of the room, she remarked, “Some shit is gonna go down tonight.” I chuckled uneasily, realizing, somewhere in the back of my mind, that she was probably right. This was more reality than carnival.

The night started off normally enough when three men wearing white T-shirts were ejected in an upper section of the arena. I jetted toward them with my camera to grab footage, just in case it got rowdy. Their T-shirts read MUSLIMS UNITED AGAINST TRUMP on the back, and as the crowd chanted, “U-S-A!” each man raised one fist into the air. No violence. There was an order to these things. Like clockwork. They were escorted out under an electronic scoreboard reading MAKE AMERICA GREAT AGAIN.

I remarked to a Slate reporter, “People think it’s new, but this has been going on at Trump rallies since at least November. There’ll be ten more of those tonight.” The back of my mind hadn’t reached the front of my lips.

What I didn’t realize was that hundreds of protesters had gathered outside. Cable news was running constant aerials of the crammed streets. The intensity started ramping up, both inside and outside the arena. Eventually, much to the shock of all of us, Trump canceled the rally about half an hour before it was supposed to start, setting off pandemonium unlike anything I had ever seen.

Scuffles started breaking out inside and outside, and protests were becoming violent as demonstrators clashed with police. I grabbed my camera and ran outside to gather footage for the network.

Suddenly, in a split second, I felt a tug on the back of my sweatshirt. Well, it wasn’t so much of a tug as it was an aggressive backward yank from multiple police officers.

“Whoa, whoa, whoa, whoa, whoa!” I yelled.

I was slammed into the ground.

“Put your hands behind your back! Hands behind your back!”

My face was bashed into the street. My camera went flying. One of the officers put his boot to my neck and handcuffed me. I could hear nothing at this point other than the sound of the arresting officer’s police walkie-talkie blaring codes.

The police officer walked away. I lay there on the street on my stomach, in shock. The entire process took about thirty seconds; I never even saw the police officers’ faces. I just knew I was in pain and that a mistake had been made. Another officer eventually came and picked me up off the ground and escorted me to the police van. I calmly informed him that I was a member of the press and asked why I had been arrested. He (very genuinely, I think) said he didn’t know. For the next couple of hours, I was in police custody. I was able to, however—somehow, while handcuffed—reach into my pocket, grab my phone, and alert the higher-ups at the network that I had been arrested.

Word spread like wildfire that I was detained. It turned out that Fox News had run video of my arrest without realizing I was a journalist, which ended up being what saved me. You see, no one could seem to explain exactly why I had been thrown to the ground and handcuffed. I wasn’t doing anything wrong. I didn’t disobey any police officers. I was a journalist on a public street doing my thing. So I was bizarrely charged with resisting arrest. Aside from the Fox News footage, my camera continued to roll. You could clearly hear me very politely asking a Chicago police officer why I had been arrested.

An unexpected highlight: The camera was in a police officer’s hand and still rolling while I was in the police van. When I retrieved the camera later, I played back the footage and heard one officer ask another about the camera. The other replied, “It belongs to one of these dickheads.”

One of these dickheads. Please put that on my tombstone.

The footage is what led the CPD to drop the charges a couple of days later. I feel certain that if Fox News knew this would happen, they would not have aired my arrest. (In a weird moment, I found out the charges were dropped because a reporter from CNN called me to ask for comment. No wonder the network bills itself as the home for breaking news.)

I was asked recently if I was scared that night. To be perfectly honest, I wasn’t. Not because I am the epitome of bravery or anything like that. Simply put, I was baffled. The entire time, whether I was on my stomach with my face looking at concrete or in the police van, I thought repeatedly: This is a huge mistake and someone is going to come along and clear this up any minute now. On top of that, I was focused on my job. I had footage to feed. It didn’t hit me how serious and potentially dangerous the situation was. During that first hour after the arrest, I was frustrated to be kept from doing the task I was in Chicago to do.

But in the meantime, I was sent to jail. I was let out later that night, and by that point, the story had gone viral. CBS ran multiple stories about the incident. My phone was blowing up with text messages, calls, and emails. Hungry reporters wanted me to comment on being unjustly arrested. Me? I was just hungry. I wanted to

go to bed.

I called my bosses at CBS to fill them in on what had happened, then went to the network’s satellite truck and fed all my footage to the New York headquarters. In the process, I rewatched the incident from the vantage point of my camera.

After a precautionary trip to the hospital, I went to my hotel room, flipped my phone to silent, and went to sleep.

You might notice a missing sentence in there. Well, I did something stupid. Or, rather, I didn’t do something: I forgot to tell my family what had happened. I was so tired that it didn’t even occur to me. When I got back to my hotel room, I wanted nothing more than for my head to hit the pillow. I didn’t want to discuss the incident or relive it. I wasn’t traumatized—many journalists have been through much worse—but it was not something I had ever experienced before.

I figured I would get in touch with my folks in the morning. And honestly, the last thing you want to do as a child of brown parents is to call and tell them that you’ve been arrested.

I can just imagine it now.

ME: Hey Ma, listen. I’m calling you from jail—

BISHAKHA: I knew it! I knew this would happen! I told you you should’ve went to grad school.

ME: No, Ma. It’s not like that. If you could just listen for a second—

BISHAKHA: What did you do? I bet it was all that drinking and drugging.

ME: What? No, I was—

BISHAKHA: It was sex, wasn’t it? You were arrested for sex. I told you to focus on your studies and not the sex stuff!

ME: I can’t believe I used my one phone call on this.

The next day, I awoke to a phone call from my father in India. I thought it was going to be one of his catch-up phone calls, where I’d be in for a few long minutes of awkward conversation about the weather.

“WHAT HAPPENED?!” my father yelled into the phone.

I said, “Oh Dad, I am so sorry I didn’t tell you. Basically, I was in Chicago and we were here for a Trump rally, and—wait a minute . . . How did you know? You live in India.”

He said, “You’re in every newspaper in India. MY SON IS A STAR!”

Our car eventually made its way to Shyamal’s neighborhood, Salt Lake (basically the Brooklyn of Kolkata), and was slowly meandering to the Hyatt, an imposing marvel hidden behind a thick layer of security. My father began offering a few scant details about the life he had lived since moving here.

“I was very extraordinarily careful about my health. It’s very important. Sports. Music. I practice piano, accordion, and vocals,” he said. There was more. He said he did yoga. And he played golf, plus tennis three times a week without fail. Jogging.

“Perhaps I haven’t told you that I’ve taken lots of interest in cosmology,” he added.

Great, I thought. My dad had moved to India and become a hippie. Maybe he’d like the Dave Matthews Band as much as I do.

“Cosmology? I’m looking forward to hearing about it,” I said with a laugh. Would it be too much to ask my father if he would smoke pot with me?

“Nowadays, I’m busy watching the sky with a binocular and everything,” Shyamal said, deadly serious. “We have a skywatch club. We meet every Saturday. You go camping twice a year to go outside and watch the planets.”

“Do you have a lot of friends?” I asked. I had a feeling I knew what the answer was going to be.

“No,” he said. He wasn’t irked by it. He was matter-of-fact, like he was when telling me about the writer Rabindranath Tagore.

“To be honest with you, I am my friend. And my accordion. And my piano. My binocular. And my books. My art collections. They are my friends,” my father said.

But Dad, I wanted to say, those are just things. But I don’t think he knew the difference. I’m not sure he ever had a friend.

“I lead a very disciplined life. Very careful life. I’m okay. Full of spirit,” he said.

Full of spirit. On this, he was right. If there was one thing he had, much to my surprise, it was spirit. This level of rejuvenation had been unforeseen on my end. I had spent the last eleven years looking for my own place in the world, and it appeared that Shyamal had been looking for his.

Five

“Sent from my iPad.”

The next morning, exhausted from the flight but anticipating what lay ahead, I woke up to an email from Bishakha.

Subject: Hi shambo, are you and Wesley enjoying the city, what have you seen so far.

Body: What kind of food are you eating, please send some photos, have fun and enjoy. Give my love to Wesley. Ma.

And underneath? “Sent from my iPad.”

Bishakha had come a long way since I was in college. During that period, we’d exchange phone calls once every couple of weeks, which was as far as her technological literacy had expanded, given that she never learned how to use a computer. The calls were warmer than the ones with Shyamal, and I always felt a bit more sympathetic toward her because she was the human equivalent of analog in a digital world. It’s hard to live in the United States without being technologically fluent—say, not knowing how to send an email. Shyamal never had that problem. (Plus Shyamal was the one who had moved away with no explanation.)

In 2009, my junior year, I had been accepted into Boston University’s study-abroad program in London. I was going to be a radio reporter for the spring semester at a small station called Hayes FM, and it would also be my first time going to Europe. It was going to be difficult for Bishakha and me to talk on the phone, both financially and logistically.

She asked me to teach her how to use email over winter break.

I was skeptical that this would work. My mother didn’t know how to turn on the computer, let alone type, navigate browsers, or use passwords, and, at the time, a cable modem. We forget that there was a time when wireless routers weren’t the norm.

But we gave it a shot.

Every day during winter break, I sat down with Bishakha at the desktop computer in the basement of our home in Howell. We created an email address for her with a simple password, and I showed her where to place her hands on the keyboard. She would insist on typing only with the pointer finger on each hand: a painstaking process. We would get very frustrated with each other. I would lose patience with her inability to grasp simple concepts, like double clicking. She would get irritated with my tone. There was an extra annoyance on my end because I knew my white friends’ parents knew how to use computers.

Bishakha made progress—slowly. It was a little like when all the famous figures from the past discover a mall in Bill & Ted’s Excellent Adventure. She was exploring this world she had never tapped into before, and there was a genuine sense of wonderment about all the fascinating things you can do on the Internet. (I didn’t introduce her to all the things on the Internet, of course.) I tried teaching her how to use instant messaging on Google, which she found fascinating. But her favorite thing about using the computer was the CAPS LOCK key. She loved typing in capital letters, the same way my dad likes speaking in them. Bishakha, of course, didn’t understand that typing in all caps means you’re yelling at someone. And she struggled with the notion of hitting ENTER after whatever she had to say. Her chats would just sit there, aimless, with no one to read them. It was, again, an apt metaphor.

She still needed me to hold her hand from start to finish. Where’s the power button on the computer? Where do I type in the site? What is my email address? Why isn’t it doing what I want it to do?

By the time my mother dropped me off at Newark Airport, I thought it was a futile endeavor. She wouldn’t be able to do this without me there.

Yet, lo and behold: When I got off the plane at Heathrow and got to my London lodgings, I had an email waiting for me. It was from Bishakha: “HELLO BABA, HOPE YOU GET TO LONDON OKAY. PLEASE DON’T DRINK.”

It must’ve taken her hours to compose, yet here she was. Bishakha had done it. Eventually, she became, er, slightly more proficient with instant messaging.

Here are exact excerpts from our very fi

rst Gchat:

ME: hi mom!

BISHAKHA: hishambo

ME: hi ma

ME: i can’t believe you figured this out

ME: i’m in class right now

BISHAKHA: what do thinki am ha ha

And a couple of minutes later:

ME: how do you like your new computer?

BISHAKHA: ilike it but i feel like that i am in dark

ME: what do you mean

ME: dont forget to press enter

ME: are you there

That was the end of that conversation—not unlike my early conversations with Wesley. After I graduated, contact between my mother and me gradually decreased. Before our Mother’s Day phone call in 2018, I tried to pinpoint exactly when we last had an extended conversation. I ran a search of all our online chats, and I found the following from 2014, our most recent, from around the time I was starting a job as a field producer for Al Jazeera America. There wasn’t much improvement in her typing over five years:

ME: hi ma

BISHAKHA: HI BABU HOW ARE YOU

ME: hi ma how are you?

BISHAKHA: I AM OK HOW IS YOUR WORK

ME: it’s going well, it’s early so i am trying to get to know everyone. how are you doing?

BISHAKHA: I AM REALLY WORRIED ABOUT YOU WHEN YOU ARE SETTLED WITH YOUR LIFE ITHINK I WILL BE OK

ME: oh mom, everything is fine right now, thank you though. . . . . don’t worry

BISHAKHA: I TRY NOT TO WORRY BUT I GUESS ITSAA HABBIT. SO FAR DO LIKE THE PEOPLE

ME: yes mom, do me a favor-hit the caps lock button on the far left side of the keyboard. . . . this way you don’t type in all capital letters

BISHAKHA: i am sorry i wnnted type it that way

Soon after that, we ceased communicating, which seems ridiculous, given the tenor of that conversation. What happened? Just months following that last chat, I lost my job at Al Jazeera America when the network initiated mass layoffs. I woke up one morning on a day off, noticed my email wasn’t working, showed up at the office, and was told to go next door to the Wyndham New Yorker Hotel near Penn Station, where a line of employees waited for the bad news. I had to embark on yet another sudden job search, a year after being laid off at NBC, when Rock Center with Brian Williams was canceled. CBS hired me about six months later for a freelance job producing for CBSN, a new digital streaming network. When CBS picked me up, I was in my midtwenties and one week away from being flat broke. Reaching out to my parents as an emotional refuge wasn’t in my bloodstream, and bringing my mother into the loop felt like it would be a burden. I was focused on self-preservation, and I didn’t have the patience to explain my situation to someone who didn’t understand my industry.

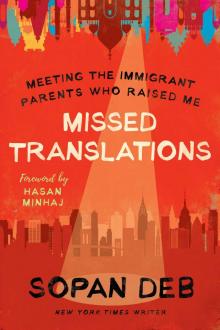

Missed Translations

Missed Translations