Missed Translations Read online

Page 7

On another level, I didn’t want to admit failure, to be that twenty-six-year-old son telling his mother that he had run out of money. In a diary I kept at the time, I wrote that I was “feeling slightly alone,” then added, “Mom doesn’t even know I lost my job.”

In 2015, CBS moved me over to the presidential campaign, which ushered in a new round of life upheaval. As a campaign embed, you don’t really sleep. You’re always in a politics bubble that even your closest friends have difficulty penetrating, let alone distant parents. And you’re always on the road at rallies, debates, conventions, you name it. This wasn’t something I could easily talk to Bishakha about, and I didn’t have time. I never even told her about the new job, because by then months of noncontact had become a year. Selfishly, I knew that being on the road so much made being there for her in any meaningful way almost impossible. I also knew that as a woman in her approximately late sixties, she was getting to the age where she needed help—say, around the house and with medical issues. She wasn’t terribly fluent with technology in a world that increasingly doesn’t allow for that. By not calling her, I put myself in an ideal position to ignore that dynamic. I put all my energy into my work, in part because that’s what campaign reporting requires but also because other parts of my life felt like distractions.

But relationships being a two-way street, I didn’t hear from her either. I did notice that after college, she sounded sadder when we spoke, but she never told me what was wrong. Sometimes, she gave the impression that she didn’t want to hear from me. Our conversations became more strained as we had trouble finding things to converse about, punctuated by frustrating disputes born from the lack of understanding of each other. The increasingly rare calls were filled with long bouts of silence. By the time I started covering the Trump campaign, she was like an old associate from whom I drifted as I tried to maneuver through a stressful adulthood. I didn’t make her a priority, and if I were to guess, this frustrated and hurt Bishakha, who, in turn, went into a cocoon of her own. Part of it, I’m sure, was financial. She was fast approaching retirement. She didn’t make much money as a cashier at a pharmacy, and she was worried about her security when she couldn’t work any longer. I have another theory: Bishakha was having difficulty with how quickly the world around her was evolving. She would express frustration about completing easy tasks online—say, setting up appointments to renew her green card or other basic Internet chores, which she didn’t know how to do. Bishakha couldn’t progress as fast as the rest of the world.

I have this old handwritten letter I received in the mail from Bishakha that came folded in a birthday card. It’s on lined notebook paper and is about a page long. I don’t know exactly what year it’s from, but I estimate it to be from about March 2012, two years before that last Gchat. This came in the midst of a particularly stormy time for our relationship.

I had to move home again to New Jersey after college because I couldn’t find work after my Boston Globe contract ended, which wasn’t surprising given how much the recession had ravaged newsrooms. I was unemployed for several months and fighting through my own millennial frustrations about how the world owed me. Three months later, I finally landed at NBC and was able to move out again. I was now living in the Gramercy neighborhood of Manhattan.

This is what her note said:

Dear Shambo,

Happy Birthday. I hope and wish that whatever you want in your life, you will get it. I always pray for you. When you were a child, you did not have a normal life like others. I wish I could do better for you. But you turned out to be a handsome, young man. And I am very proud of you.

Ma

It’s one of the few things I have from my mother, the first and only example of my mother’s acknowledgment of the difficulties of our family dynamic.

She struggled with depression as I grew up. It manifested itself in various ways, but whatever form it took, the result was anger and tears. My best reasoning is that she was a deeply isolated and lonely individual, trapped in a failing marriage and getting through her days without feeling unconditionally loved. In Howell, there wasn’t a sizable Indian community for Bishakha to be a part of. There was no escape from the unhappy home for her. Whereas Shyamal had an engineering career he had built over many years, and Sattik and I had college and our careers to look forward to, she had nothing of the sort.

When I was growing up, my mother had trouble containing her frustration on a day-to-day basis. Sometimes she would snap at the flip of a switch over something minor—say if a radio was too loud or a room was too messy for her liking.

Other times, Bishakha’s frustration went to a darker place. She would take out her anger on Sattik and me by creating an exceptionally cold dynamic in our childhood home. Coming home from school was like coming back to a roommate who you knew didn’t like you; it wasn’t bad enough to transfer rooms (or schools!), but you had to wait until graduation.

A therapist I saw once—not Sleeping Jerome—told me his theory about people and relationships. According to him, there are three types of people. There’s Type 1, who grows up with some sort of childhood trauma or currently lives within an emotionally challenging environment, which creates an emotional hole in that person. He or she will spend his or her life trying to fill that hole. That’s why people might settle for being in relationships they shouldn’t be in or putting up with unfortunate behaviors from significant others. There’s Type 2, who has those same deficiencies and that same hole, but will protect the hole rather than trying to fill it. The Type 2 won’t get close to anyone, and anyone who tries to get close will be pushed away. Type 3 is the well-adjusted person, who may have experienced trauma or may have come from a foundation of love and warmth, but knows in any case how to properly give and accept love.

Bishakha is a Type 2. She pushes people away. She pushed me away by frequently saying that she didn’t feel anyone in the world loved her, then going to her room and shutting the door (literally and figuratively). When she was feeling her worst, she made cutting remarks designed to create distance between us. She is, overall, a kind person who has struggled with showing it consistently.

The ultimate expression of warmth among loved ones or friends, outside of saying “I love you,” is “How was your day?” I realized that recently, thanks to Wesley. She always inquires about the mundane goings-on of my day, which shows a level of investment in me that would leave a great gap in my life if it no longer existed. On an emotional level, some of the most intimate moments I have had with her resulted from our sharing the dumbest things about our lives, not just the big events.

Bishakha never asked me about my day when I was young, nor did I ask her. Shyamal never asked me, and I never asked him. Bishakha and Shyamal never asked each other. Same goes for Sattik with each of us. The Deb family household would have been so much different if we asked each other to run down our respective days, just like my friend Shaun’s family did. Instead, the four of us lived in four corners of the house, finding our own outlets for our sadness and clawing at the outside world begging for release.

My family’s struggles all came to a head in eighth grade, when I was thirteen. Shyamal, Bishakha, and I were on our way to a family friend’s house. And as was characteristic for my father, he got lost. It led to an argument between my parents, which was also normal. But something seemed different about this one. Bishakha and Shyamal were viscerally angrier. My mother was shaking and crying. My father slammed his hand on the steering wheel. Over what? His getting lost? It all seems so silly now. If Shyamal used GPS, would our family have been fine?

When we got home, my mother locked herself in her room.

She stayed there for approximately six months.

I barely saw her for the rest of eighth grade.

She only came out of her room to occasionally make herself food or go to her job at Drug Fair, the pharmacy where she was a cashier. We were all isolated, but this was a level unprecedented in our household. Suddenly Shyamal was thr

ust into the role of being my primary caretaker. He began cooking and cleaning the house, in addition to his engineering career. It was only then I realized the depths of my mother’s depression and, perhaps, her fear of the outside world: She could not bring herself to leave her room to face it.

I was stewing too. I was acting up in class—what I eventually realized was a combination of puberty, trying to make friends, and bafflement about what was happening at home. I didn’t check on my mother, perhaps fueling her cycle of belief that no one cared about her. This was, of course, not true. I did care about her. I cared about Shyamal too. But I didn’t know what was going on. And I was just trying to get through school.

Shyamal was overwhelmed, dealing with an unruly son with whom he barely had a relationship. I was openly hostile to him, and my petulance, instead of distance, became the defining characteristic of our relationship. For example, I played the piano for our eighth grade musical at Howell Township Middle School South—My Fair Lady, I believe—and the cast party after the show was at an Applebee’s near our house. I asked Shyamal if I could go. He said no—reasonably so, because it was late and he couldn’t come pick me up.

I shrieked. I started throwing papers in our family room. How could you not let me go? Who are you? You’re nothing. It was totally unacceptable behavior on my part. There was stuff like this every week. Sometimes I would get physically abrasive with Shyamal. I was just so angry all the time. We all were.

I stormed out of the house, even as Shyamal yelled at me not to, and walked to the Applebee’s, staying there with the show’s cast, munching on mozzarella sticks, boneless buffalo wings, and whatever other chain restaurant appetizers the place had. The party lasted till one in the morning, and I left to walk home. Mind you, I was in eighth grade.

As I left the Applebee’s, I heard a honk in the parking lot.

Shyamal was there, waiting in the car. He had been parked there for hours, making sure I didn’t have to walk home by myself.

I didn’t say a word in the car ride home.

Along with “How was your day?” “I’m sorry” is an essential expression for loved ones. I never said that to my father. I should have apologized to him that night. Or the other nights, when I let my bitterness take hold. I should’ve said “I’m sorry” to my mother too.

One school night, I was playing on the computer in the basement of our house. The basement was my sanctuary. I never had a Super Nintendo growing up, so I had downloaded an emulator on our desktop that could re-create Nintendo games. It’s where I played various versions of Pokémon or straight computer games like Star Trek: Elite Force for hours. I had played so voraciously that I got thirsty, so I went upstairs to get a glass of water.

As I emerged at the top of the stairs, I did a double take. There were multiple police officers at my front door and flashing lights outside.

One of them saw me and said, “Did you see what happened?”

Was I dreaming?

I said the first thing that came to my head. “No, did you?” I responded. I thought for a second that something had happened outside and the police were looking for witnesses.

I turned around, and there was Shyamal walking out of our living room, being led into a police car while Bishakha frantically got into her car. She was headed to the station too. The police were looking for witnesses—witnesses inside the house. Within minutes, I was by myself.

I never learned what happened, and I don’t care to know. It was emblematic of my approach, remaining blind to this massive, traumatic occurrence in my own family. There seemed to have been some sort of confrontation between the two of them, and somebody called the police. It wasn’t the first time this had happened in our family, but it hadn’t been this bad in many years. I still remember the next morning, taking the bus to school, fielding questions from kids on the bus who wanted to know why the police were at my house. I genuinely didn’t know what to tell them.

But this time it marked the end of my parents’ tumultuous journey together, a failed experiment that lasted decades longer than it should have. Shyamal and I would never live under the same roof again; my parents officially divorced when I was a junior, roughly three years later.

Bishakha emerged from her bedroom and reasserted herself in the household, away from the stresses of a failing marriage. Shyamal was living in an apartment a short drive away. Both, perhaps feeling a taste of freedom, made earnest attempts to connect with me. Shyamal took me out to eat once every couple of weeks. Usually we’d get Chinese. You know what he’d say?

“How was your day?”

I didn’t appreciate it then, but now I realize that he was trying. So was my mother, who gleefully attended the high school musicals of which I was a part. Not that she couldn’t before. She just seemed happier now.

Meanwhile I started living life, essentially, on my own. I stopped caring about what my relationship was with them. A friend of mine who had his license taught me how to drive. When I was fifteen, I got a job at Pathmark, a local grocery store, and eventually saved up eight hundred dollars to buy a 1998 Ford Escort with faulty brakes. I crashed it within weeks. So I saved up another eight hundred to buy a 1989 Honda Accord with 150,000 miles on it. During senior year of high school, I crashed that one too, by absentmindedly driving into a fence by the track field. Then came another eight hundred, and this time the car was a relatively recent 2002 Chevy Cavalier.

As often as I could, I’d drive away from the house. (I know, I should’ve stopped driving.) I’d go to the mall. Go to Applebee’s. Starbucks. The movies. Whatever. I worked several different retail jobs, and started dating.

I was ready to be away from both of them, just as they were both ready to reconnect with me, at least as best as they knew how. With Shyamal, it was the dinners. With my mother, it was being out of her room.

In 2016, I heard from Bishakha twice: Once was after I was arrested covering the Trump campaign, when she called the next day and told me she was worried sick; and the second was when I got the job at the Times. She had received wind of the press release that went out announcing the hire and wanted to congratulate me. Both conversations lasted only minutes. In the case of the Trump arrest, I assured her I was fine but that I had to go.

It meant a lot that she would reach out, but I was not in a headspace to fully reintegrate her into my life. The stresses of covering a presidential campaign did not allow for emotional family reunions. I didn’t get there with her till that fateful Mother’s Day of 2018, when I finally picked up the phone to call her and set a lunch date.

I didn’t know it at the time, but Bishakha’s apartment is very similar to Shyamal’s in India. It is on the second floor of an apartment complex just off Route 9, a busy highway that runs through various suburban New Jersey towns and is referenced in Bruce Springsteen’s “Born to Run.” There was a golf course adjacent to the complex, although I was certain that my mother wasn’t the type to don a golf cap and grab a nine-iron.

As Wesley and I got to Bishakha’s door, I took a deep breath, then knocked three times. The door wasn’t locked, so I let us in.

“Hello?” I said.

I heard a voice in another room.

“I’ll call you back. Shambo is here,” Bishakha said.

My mother emerged, with a high-pitched singsong voice, and a slight limp.

“Hi Baba! How are you, Sona?” she said, using another pet name, roughly translating to “my precious” (not like Gollum).

“I’m good. Hi Mom,” I said.

Bishakha started speaking in Bengali. “Oh my god. How many days has it been since I’ve seen you?” she said, before enveloping me in a big embrace. She let out a deep sigh as she hugged my waist. I am probably a foot taller than her. With her arms clinging to me like barnacles, she asked me how everything was going.

Well, Mother, if you must know. I decided to embark on a journey to reconnect with both of my parents with whom I had virtually no relationship growing up. One moved to a forei

gn country without telling me and one has me in a bear hug as we speak.

“Good. This is Wesley,” I said, indicating my savior, who seemed not to mind drifting into the background.

“Hello, Wesley! How are you?” Bishakha immediately let me go and turned her embraceable arms toward Wesley.

“It’s so nice to meet you,” Wesley said.

We handed Bishakha the homemade double-chocolate crinkle cookies and flowers we brought for her.

“Oh yeah! Thank you! I’m so glad you could come. I’m really so happy to see you. Please sit down. Are you guys hungry?” she said. Her voice was sharp. I wondered when was the last time she had received any gifts from anybody.

Bishakha began preparing lunch. She had made my favorite mustard fish curry from when I was a child. I was struck by how empty her apartment looked: There was barely any art on the walls, and some shelves had nothing on them. There were no pictures of Sattik or me, or anyone at all. It was almost like no one had been here for months. My childhood piano was still there.

Her apartment had two bedrooms. I remember visiting once when she first moved here, probably around five years prior. There was a cozy porch where Bishakha said she read books. She also said she often took walks around the neighborhood for exercise.

“Oh Sopan, can you do me a favor?” I heard Bishakha say from the kitchen. “Remember my phone? It’s an old phone number?”

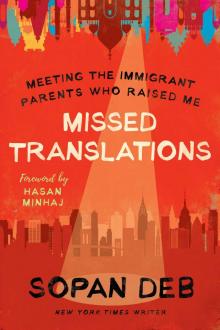

Missed Translations

Missed Translations